Oil and Gas Groups Under Pressure to Plug Leaks

Boom

times for US oil and gas have shone a new spotlight on an old problem: leaks of

methane, a powerful greenhouse gas.

Persistent

leakage of its main constituent undercuts the claim that natural gas helps

economies shift away from more polluting energy sources.

While

US energy-related carbon dioxide emissions have declined as natural gas

displaces coal at power stations, methane emitted by the oil and gas sectors

has not.

Aside

from the climate danger, oil and gas companies say they would rather make money

by selling it.

Quantifying

volumes is difficult, however. As US energy industry and regulators attempt to

rein in methane emissions, they are grappling over the best ways to measure

them.

The

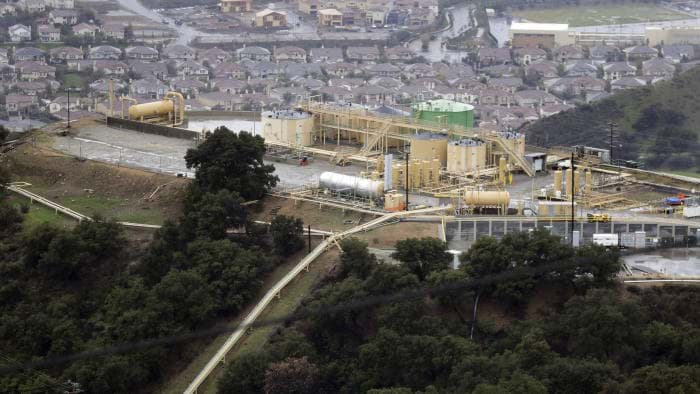

most notorious recent leak took place over four months in 2015-16, when about

5bn cubic feet of gas seeped from the Aliso Canyon storage site in Los Angeles.

But many leaks of the colourless, odourless gas are dispersed and sporadic,

evading detection.

Official

inventory data from the Environmental Protection Agency show that between 2005

and 2017, methane emissions from US petroleum systems climbed 2.5 per cent to

1.5m tonnes, led by growth from upstream producers. Emissions from natural gas

systems declined 3.4 per cent to 6.6m tonnes over the same period.

The

EPA data are based on a “bottom up” approach of estimating emissions at

individual sites and extrapolating them to the whole country — a method with

limitations, according to a 2018 government-sponsored study.

Guidelines

for checking inventories have not been updated since 2006 — before fracking

transformed US oil and gas production. Bottom-up measurements are taken only

periodically, “so if the emissions occur in a burst at midnight, no one is

there to measure it, you haven’t captured it and you come to a false sense of

the emissions reading”, said James White, a professor of geological sciences at

the University of Colorado Boulder who chaired the study.

Another

“top down” approach uses sensors on aircraft, satellites and towers to estimate

methane levels in the atmosphere. But the network of sites is “sparse”,

according to the 2018 study, and it can be difficult to trace emissions’

sources.

Timing

is also a drawback of atmospheric measurement. Leaks can rise and fall with gas

volumes, for example when heating demand is high during a cold snap. “One thing

that can be problematic about the ‘top down’ approach is that you’re assuming

operations are steady-state and constant. That’s just not the way that we

necessarily operate,” said Sandra Snyder, senior regulatory attorney at the

Interstate Natural Gas Association of America, a pipeline industry group.

Recent

studies have shown “conflicting results” on the trend of methane emissions from

oil and gas operations in the US, according to a 2019 paper by scientists at

the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which itself found a

“modest increase”. But another paper co-ordinated by the Environmental Defense

Fund, a campaign group, found methane emissions from the oil and gas industry

were at least 60 per cent higher than government statistics suggested.

Under

President Donald Trump, the EPA has sought to loosen standards for methane

leaks from the oil and gas industry. Among its proposals, bigger oil and gas

wells would need to be monitored once instead of twice a year — a plan

supported by many in the industry.

Environmental

groups oppose the change. Mark Brownstein of the EDF said a large portion of

emissions was coming from a handful of sources, often from equipment failure or

worker error. With more frequent inspections, “you’re constantly on the lookout

for situations where the equipment is not operating as designed”.

Technology

to find leaks has improved. Optical imaging cameras that detect traces of gas

can be mounted on drones, for example, reducing the cost of visiting far-flung

well sites.

The

industry has announced voluntary measures to address methane leaks. The Oil and

Gas Climate Initiative, an international group of upstream producers whose US

members include Chevron, Exxon Mobil and Occidental Petroleum, in September

committed to cut methane lost to the atmosphere below 0.25 per cent of gas sold

by 2025, down from 0.32 per cent in 2017.

The

One Future Coalition, a group of US natural gas companies, has outlined a goal

of cutting methane emissions to less than 1 per cent of gross natural gas

production and delivery, which the group contends would provide “clear and

immediate [greenhouse gas] reduction benefits as compared to any other fossil

fuel in any other application”.

The

Environmental Partnership, formed by industry lobby group the American

Petroleum Institute, aims to cut methane through technical fixes such as

replacing control valves powered by escaping gas.

Christopher

Smith, a senior vice-president at Cheniere Energy, the biggest US liquefied

natural gas exporter, said stricter regulations and better practices could help

the country compete in world energy markets.

“It’s part of our value proposition, part of our business model, to be able to differentiate natural gas coming from the United States.”